|

|

|

| Fourth Marines Band: "Last China Band" |

|

MIKADO NO KYAKU (Guest of the Emperor) |

| Chapter Six - The Nissyo Maru, A True Trip of Terror - Page 67-81 |

| Chapter Six The Nissyo Maru, A True Trip of Terror After a light breakfast which was nothing more than a tiny ball of sticky rice, the big gates of the old prison opened and we marched out into the nearly deserted city street. I was surprised how near it seemed we were from the Manila docks, for we were soon there, standing in ranks. In the distance, we could see Corregidor - that little black bump on the horizon to which MacArthur had not yet returned. Another large group of prisoners from the Port Area work party was waiting for us. Together in the two groups there were about 1500 of us ragged looking, strangely clad, bone thin, weary warriors - already survivors. There were many among us that had no idea of what we faced in the mottled, rusty-red transport that was moored to the dock in front of us: the Japanese ship Nissyo Maru. It looked as though it could accommodate no more than half of us. We stood most of the morning in the dock house. The Japanese guard came to us one by one. They asked if we had any knives, matches or pencils; then, made us open any packages, quan bags and the clothes we were wearing to see if we had any of those items. Those prisoners who were found to be carrying cigarette lighters, scissors or razors were beaten on the spot and the stuff confiscated. In a long single line we then marched over the gangplank, stretched up and over the brown oily waters in a hell ship. I could see some commotion on the deck ahead. I came to a gamut of Japanese soldier guards and recognized one of them as the notorious "Mickey Mouse" From Military Prison Camp 1. He was given that name because of his huge ears and mousey-like personality. He knew and could speak a little English and was curious why he was called Mickey Mouse. When told that it was because he was a lot like a famous American motion picture star, he accepted his "handle" gratefully. But, Mouse was not grateful this day. Rather he was shouting like crazy, "Take off shoes! Throw in hold! Hyyaku! (hurry) All bags too! Now! Go down ladder, speedo! speedo!" He punctuated his urging with shoves and pushes with his rifle butt. The men he struck pushed those ahead and terror struck others close by as they hurried to get into the hold on to ladders as bags and boots bounced off heads and backs of the hapless men trying to get out of the way. We moved on as others poured onto the deck behind us to receive the same brutal welcome. The orders were repeated in staccato. "Air Raid", another even more notorious Camp 1 guard joined the Mouse at pushing, shoving, and hitting the men scrambling to come on to the ship and into the hold. |

|

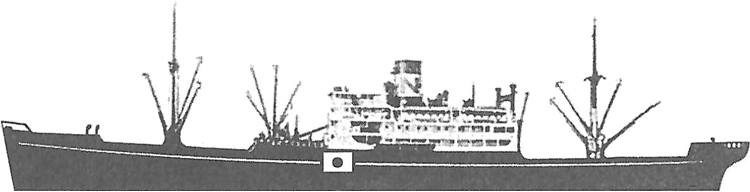

| Nissyo Maru |

| Subhuman Cargo... My shock had little to do with the roughness even though I had no idea this was the standard method for loading a Japanese vessel with its "subhuman" cargo. I was more concerned as I scrambled down the ladder to find the hold was already crammed full, as far as I could see, with half naked, sweating men in ragged, beige-colored tatters. The quan bags and footgear had already become a pile twice the height of a man. Nearly 700 men had already entered the hold before me. Behind was another 800 more to come. There couldn't be room for their baggage, much less the men. But our captors kept shaking us down, like one shakes down the garbage in a bag to make room for more. And that's what we were to them - garbage. I was pushed back away from the opening of the hold. My eyes became accustomed to the half light; under the covered part of the compartment, I could see wooden tiers for sleeping. They stood one above the other, five or six feet high, with an 18 inch clearance for each, like cages for animals in a pet shop. I wedged myself into one of the slots. It was very close even for a little fellow of five feet and six inches, like myself. I found I couldn't so much as raise my elbow and, with more and more men crowding in, there was no escape, no way to back out. I was trapped. It was apparent the guards intended each box in the array made for one person to hold five or more prisoners. I could hear them counting. Others squeezed in to escape the rain of shoes and stuff still coming down like hail from above. The racket from the yelling and shouting was deafening back in the slots. I tried to listen and make some sense of it over the racket. "Oops ... What's the matter ... He's fainted ..." That was just the beginning. As the newcomers jammed into the hold, those who had been there 40 minutes, 30 minutes, 20 minutes began to drop. Well, rather they slumped in their faint. There was no room to fall. Those who still had their wits about them in all that bedlam, sought to push the weak back up to the deck; a thinner outgoing stream of limp humanity met a forceful incoming flood of men leaping downward away from the frantic gamut above. "Air Raid" frantically tried to wear himself out beating at the flow of prisoners trying to move in both directions. He seemed to be inexhaustible. Obviously, he thought, some of the limp were pretending. Maybe some of them were faking unconsciousness; most were not and none was not terrified. As others reached the fresh air above and were revived, they were redriven back down into an already fully packed mass of flesh and piles of stuff below. The once cool morning had now become a blazing midday inferno as the tropical sun in a cloudless, July sky bore down on the steaming scene of misery in Manila. The old, rusty, converted collier absorbed the scorching heat; it was like being on the inside of a giant steam iron. We cooked and I felt myself being pushed deeper into the sleeping slot, farther and farther away from the air and the light of the opening. The bedlam subsided to a hum in my ears; the hold turned gray. Without orders from the captors, a few brave and desperate men snatched up the hatch covers from beneath them and began tumbling the baggage into the hold below. Doing so made a little more room for those still stumbling down the ladders, but offered little relief for those already crammed into the space not larger than half a tennis court. Even the most ignorant Japanese guard must have known it would be an impossibility to stuff all 1500 of us into such a small hold. They tried their damnedest, nonetheless. Outside my crevice-like slot, men were still slumping. We who were motionless and not struggling were still soaked with sweat - our own and that of our fellows. Water dripped on me from the slots above. I thought at first some poor duffer's kidneys had failed him or that a canteen had broken open. Perhaps so, but most of it was sweat. I sweat! And the stench! God! The stench! "We must have more space! More space! It would be better that we be shot now! We must have more space." It could have been hours - maybe it was only a few minutes - for the American interpreter to convince the Japanese that 1,500 men couldn't be jammed in such a small, hot space and expect them to live very long. But it took long tortuous hours for our hosts to do something about it. After sundown, the guards yelled down for all men whose numbers were below 700 to climb out and go to the forward hold of the ship. Such a scrambling over each other, and under each other! Finally those left behind found themselves with a little more space; it was precious little. It did make breathing a little easier. Those that went forward tried to scoop up lungs full of cooler evening air before going down the ladders into the slightly larger hold. Again, the guards urged every one along with little less frantic intensity even though they had been at it for hours and hours. I was among those moved forward. There were no sleeping bays, just solid iron decks surrounding another hatch, covered with huge planks fitted with metal bands and hand-holds, directly beneath the opening overhead. It seemed larger on that account and probably was; there still was not room for all to sit at one time upon the hard decking still warm from the blistering heat of the day. To have enough space to lie down and stretch out was out of the question. Out of Control... The noise from all of us yelling and screaming just never stopped. Everything was out of control. Officers and others who tried to get the group to quiet down and organize things were shouted down. Men who tried to claim a bit of space to stand or sit were shoved about in all directions. "This is my spot!" one would proclaim of a square not much larger than his two feet. "The hell it is!" an offended neighbor would yell back as loud as he could. But the sound of his voice could not be heard five feet away as it would be drowned out by the yelling there. Men in one quadrant of the hold would find themselves in the one opposite without having made any effort to move at all. The mass of flesh just seethed around like so many beans in a boiling pot. It was sheer bedlam and pandemonium all through the night. Little by little a tiny bit of order emerged. The few older officers, some of them doctors and chaplains, managed a little control. It was very difficult for them. Chaplain Stanley Reilley's effort is memorable and heroic. He made himself heard and it helped, but there were others who tried. The following day, enough water was lowered down to us by selected prisoner helpers up on deck so that each man got about a half pint on two occasions. A bigger problem was what to do once it ran through one's system. There were no convenient latrines at all, not until a large wooden tub was lowered on ropes to become our night chamber. It was quickly filled and sometimes overflowed before being drawn above and disposed of over the side of the ship as a growing long line formed around the perimeter of the hold to wait its return. It made a mess around the tub that is beyond description. Those unfortunate souls near it pressed hard against their neighbors to get away from it. The line never ended and stood for the entire seventeen days we spent aboard the Nissyo. The tub was hauled up, emptied and lowered down again, each half hour, 1000 times or more. Some Medical corpsman were detailed to handle the nasty chore in round the clock shifts. There was no shortage of volunteers for the job however, because of the opportunity to be on deck in the fresh air, and out of the teeming, hot mass of sweating bodies below. It was a necessary but filthy mess, particularly for those in the vicinity of the operation. Because of the motion of the ship these prisoners were subject to many unfortunate accidents. A few latrines were available up on deck built out beyond the gunnels, but only a lucky few were able to ever use them once they managed to get topside. It was a great relief to the men huddled so tightly together in the ship when, after another long, hot day, the ship moved away from the dock. The throb of the engine could be felt as the decks and bulkheads creaked and vibrated. But all shuddered with it. The sooner things happened, the sooner we could get off this terrible vessel. Then, after a short time, we shivered with despair for we heard the anchor chain rattle out of its locker as it was dropped. We soon knew we were standing just a few miles from Corregidor. There the ship sat and sat - and sat - for four, whole, hot, sizzling days while we stood and slumped against each other watching the yellow bucket running up and down regularly to and from topside. Our beards growing bristly for lack of razors and water to cut them. The rumor was that our ship was waiting for the formation of a convoy. Men began to work out ways for some to sit a while. In my turns I, fitfully, slept a little. This was complicated by some space ruled off for a "sick bay". In this space, those who were determined to be sick were allowed to stretch out and lie down. This made it ever more crowded for the others. There was some compassion for those still worse off than others - it was not a lot. Small quantities of steamed barley were lowered to us twice each day along with the little bit of drinking water - a half pint for each and it was not enough. Men became desperate for water and attempted to trade their little ration of food for water. Those who were too dry to eat soon found someone too hungry to eat. A strange thing occurred. The "dog eat dog" attitude so prevalent within the camps seemed to disappear in this awful, seething mass of men. "Here, Joe, you need it worse that I need it..." was sometimes heard. I saw trembling hands of one shove canteens into another's ghost-white lips. We heard the anchor being pulled up and the ship moved again. I wish we could say we felt a little breeze coming through from above. The men all joined in a great deafening cheer which grew louder, ultimately growing into a roar - like a capacity crowd at a championship football game as the favorites come trotting onto the field. There was no place for the sound to go so it came right back at us. God knows why we were cheering, just the encouraging thought and hope that our terror and desolation would end soon. Any change seemed welcome. Had we known what was to happen to the Oroyoku Maru, The Brazil Maru and the other hell ships that tried to come after us, and were even more terrifying and sunk with great loss of life, we would not likely have done so. Again, going on to anywhere was preferred to just layingto, broiling in the sun. Whatever it was we talked, we shouted, and our ears rang with the sound of our own voices; the confusion went on all night. The Japanese guards wearied of it and told us to shut up or they would shoot, but we didn't and they didn't. You could tell by the roll of the ship that we were out of the bay; out of sight of the black rock of Corregidor that had once been our sanctuary and lost hope of victory. Out into the great, blue, South China Sea. We could only imagine what it looked like and where we were headed - God only knew where. Now, as men seem always to do, we tried to build ourselves communities. A few of the inventive made hammocks in the overhead. Others staked out imaginary claims on sitting space. Since there wasn't nearly enough to go around, there were always arguments as to whose posterior was covering whose spot. The men with the larger behinds caught the most hell. There were even some fights. Not because anybody was really angry but, just because emotions had bulged up like balloons, too full of air. They had to burst. After a fight, everybody would sit quietly for a while and then "Hey, you, son of a bitch, who the hell ..." "Who's calling me a ..." And another fight would begin. The ship plowed on and on through smooth seas, rough seas, choppy seas. The sun rose and the light came through the hatchway and zigzagged wildly around our pen as the ship followed a defensive course to avoid our American submarines. The sun set. The noise, the din and stench went on all night. We watched the heavens through the hatchway and tried to make them out. But, they skewed across the deep blue-black field like shooting stars, first in one direction and then, as the ship turned, scooted back again. Watching them kept your mind off the possibility of a raging torpedo smashing into the thin hull of the old ship and blowing us into kingdom come. The sun rose and there was light again. I thought of the times that tourists had paid hundreds of dollars to take this very trip from Manila to Japan in luxury and comfort. The food situation was not ideal, but we had all been in worse situations. Cooked barley, sometimes with a little rice, was lowered on ropes in the same kind of buckets used to lift out the waste. We hoped they were different ones. Each bucket was intended to feed 150 men, according to numbers. Control was just impossible and some men got more than others. The weaker and sicker ones got the least as the stronger ones crawled over them to get a second helping. Some men died, their already weakened bodies unable to bear the stress and conditions on the Nissyo. During the day, their bodies were taken up on deck and slipped into the sea with Chaplain Reilley committing their souls to the Almighty. Several prisoners went berserk and had to be held down until they became too weak to resist. The first leg of our miserable journey took us north along the west coast of Luzon and then across to the Formosan Strait to the west of what is now Taiwan. Conditions did not improve greatly enroute. The noise, the filth, the smell and the tension went on 24 hours a day in my hold. I expect it did in the aft hold also. After a day or so, a few men were allowed on top deck for a short time. A gulp or two of fresh sea air can be refreshing on any cruise, but on one such as ours it was as precious as food and water. I made it to the top deck several times on this part of the trip and was rewarded with a salt water bath from a pressure hose played on us by some of the ship's crew of Japanese civilian sailors. The only bad part of that was then having to go back down in that stinking hold again. I spent some of my time weaving my way around my half-naked comrades trying to find and visit with friends. That is when I was not waiting in line for my bit of rice and water or the other line to get rid of it later in the old scum bucket. I found only a few: There was Technical Sergeant Jack Rauhof, the drum major of my outfit, the 4th Marines Band (more lately known as the 3rd Platoon, E Company, 2nd Battalion), Privates First Class Monford P. Charleton, S. W. Stephens, and John P. Latham. All former bandsmen. Another, Leland H. Montgomery, was also aboard but I didn't know it at the time. He was one of the Manila Port Area work detail that had been waiting on the dock the day we boarded the ship. It was Montgomery who helped me considerably with information about the Nissyo voyage. He remembers details about the ship and the trip, often in a different way than I do. But as he explains it, "Everyone saw his situation from their own point of view ...". We do agree that it was a very miserable ordeal from the first hour in Manila to the last moment in Moji, Japan. The ship had been made in Europe and sold to the Japanese sometime well before the war. Montgomery remembers seeing a bronze plaque labeling the vessel's origin, size, and other details. He thought it was a rather modern ship designed originally for carrying cargo. It was fitted with booms and winches to lower and remove stuff in nets. For sure it was not well designed to carry large numbers of troops at all. New Friends... I also made a new friend or two on this not-so-pleasurable cruise as well. Strangely they were staff noncommissioned officers and older than myself but the condition of being a POW had a leveling effect on men, who in normal circumstances, would not become close friends. Staff Sergeant Michael Oss and I shared the same two or three square feet of iron deck for almost the whole trip. He saved my spot for me and I saved his for him when we had to leave it. We slept leaning against one another when we could both get room to sit, otherwise one would sit while the other stood and tried to keep the pack from trampling upon us. I met Staff Sergeant E. D. Smith who was old enough to be my dad already and reminded me of him sometimes. He was quiet, stiff and had a hard as nails personality. He demanded respect with a bearing that he carried with him despite his terrible degradation. Why we hit it off, I have no idea. We became warm friends until his last days soon after the war. He helped bolster my courage and strength to endure not only the hell ship experience but the remaining year of our captivity. Our first port of call was Takao, Taiwan. We were surprised and exhilarated by the complete opening of the hatch over our heads and being allowed to climb out and scatter ourselves around the forward well deck. It was refreshing to see the green hills that formed a colorful background to the port area docks where we were tied up. I tried to imagine what might be going on out there in what appeared to be a very beautiful place. Of course, most any place looked mighty nice when compared to the inside of the ship's hold. The hatch was opened on the deck of our iron stateroom in order that the crew and some native stevedores could lower many 56-kilo bags of brown sugar into the hold underneath. We spent the loading time watching the boom, winch and net operators hoist the bags up from the dock to which the ship was tied and lower the sweet stuff into the ship. We hungry men wrung our hands waiting for the time when, after we had gotten underway again, that we might get our hands on some of it. Looking around on dockside, there were warehouses as far as we could see with huge Japanese character writing on the walls - writing in blue and green that we couldn't understand. There were stevedores in blue denims with little, white towels wrapped around their heads, women in pantaloons and men in shorts, and Japanese sailors and soldiers eating bananas and carrying little boxes on and off our ship goodies we supposed, the things soldiers and sailors crave at sea and go wild for when they first get ashore. There was none of it for us. We'd be lucky if we could just get to some of the sugar. I was fortunate to spend a little extra time up on the deck while the hatches were open and the ship was being loaded. I even had my little ration of rice up there in the clean air - strange smelling because it was fresh. It was hot - but it was clean, like Nebraska in summer. Thirst was a problem. No one came around and issued me any water in a canteen cup I had somehow acquired. I crawled beneath the workings of a steam winch that was not being used at the time, more to hide than anything else, so I wouldn't have to return to the ship's hold. I found a valve leaking live steam against the heavy metal and water was condensing off of it. Holding my cup under the drip, I eventually collected about a half cup of water. Except for a bit of oil, it was pure, warm and refreshing. I stayed as long as I dared. As I returned to my place in the hold, I caught a blast of the foul air and of the yellow bucket. It shook me to my bones. "To the rail, you fool! into the water!" something said inside of me. I shook my head and drowned the temptation. Considering where I was I didn't have a chance in a million for escape. Furthermore, my effort would have been worse for the 1490 or so others in the crawling mass of humanity that lay below. The shooting rule of 10 for one still held. Maybe this time it would be upped to a 100 to 1. I couldn't be responsible for any life but my own. "You're insane not to do it." I was saying to me as my feet went step by step down the ladder. "You're not in your right mind to go back." Then, I was down, with my tortured fellow beings, still talking to myself. Most of us, realizing the futility of battles, had stopped fighting with one another. We tried to play cards. But there wasn't really room for that. And anyway, have you ever tried to hear a bid, or a bet, or a call over the roar of 750 men? "Anyone with leadership could take over this ship. ANYONE with leadership. You don't have the guts. We outnumber them seven or eight to one. YOU don't have the guts!" But my sane self answered. "There's nobody among us that who knows how to run this ship!" Then I felt better. Some of the men couldn't wait to get into the sugar and went to help themselves. That was a foolish thing to do. Too much sugar dries a person out and there was not enough water to go with it. I had a sweet tooth and the temptation was great to eat all that was offered me; it was all I could do to keep my self control. I didn't want to develop a case of diarrhea either what with the sanitation facilities being what they were. Our hosts had warned against thievery of the sugar and threatened severe punishment. Fortunately, nobody was caught. Those of us who could see the midnight blue sky through the open hatch of our hold knew that dawn had not yet come when we were pulled away from the dock and left Takao harbor and chugged northward. We rolled, we pitched, we moved along in a not so gentle sea, up and down, up and down, back and forth...proceeding. As our beards grew, we could see the blue sky above the open hatch, then the midnight sky. It was my turn to sit close under the hatch and look at the deep purple above like a giant television screen filled with the light of a million stars. The date was July 26th, 1944. I had no watch but I learned years later it was nearly 2:11 AM. I leaned back against the legs of my new found shipmate, Michael "Mike" Oss. Suddenly, the "screen" turned red, blotting out the stars and melting the deep purple. Almost immediately we heard it - "Boom!" The ship shuddered as it veered sharply in another direction. When the stars appeared again they skewed across my view indicating that the ship was taking another heading. Obviously it was being put in a sharply, zigzag motion. Under Attack... Another big explosive flash shot across the sky. This time large shadowy chunks of what had once been part of a ship sailed across the field of view. Already our ship's siren had sounded, and guards were rushing about the deck above us, hurrying to cover the hatch in case we all tried to evacuate the hold. Escorting destroyers in our convoy began to discharge depth bombs, some close, some far. What had happened? Well, obviously, the convoy was under attack by submarines. A ship nearby us had been struck and, my first thought was that it was an oil tanker. Nothing else could have made such a blast. It was many years later that I learned more of the story. In the book, "Silent Victory", by Blair, I found the account of this strike. It had been made by the USS Crevale commanded by Frank Walker; the USS Flasher commanded by Ruben Whitaker; and USS Angler commanded by Franklin Hess. The Flasher fired all six of its remaining torpedoes. One ran through the convoy formation, probably narrowly missing our fragile Nissyo Maru and had sunk the Otoriyama Maru, a 5280 ton oiler. Not all the booming sounds of explosions that continued during the night were made by depth charging escorts. The pack took another freighter, the Tosan Maru down later in the morning in what must have been a far larger convoy than we had imagined it ever to be. It was an exciting night and one that proved that a super, divine, guiding hand must surely have watched over us. A few more of our comrades died in the remaining days at sea enroute to Japan. Dysentery, malaria, and dehydration plagued us the rest of the way in our iron dungeon with red-lead walls. Large water blisters broke out on the bodies of nearly everyone, attributed by the knowledgeable, to the closeness and lack of any means to keep clean. Those who had contact with our guards complained and so instructions were passed to count off groups of 20 men. "Come topside." It was one of the few orders given by the Japanese that I ever heard cheered. Up the ladder we scrambled, those of us who still had the strength to climb the red iron rungs. Some did not. A hose played on us. We shivered with pleasure from a forceful stream of water pumped out of the azure blue sea. I washed my only T-shirt in the salty stuff but, instead of trying to dry it, I rolled it up around my neck to keep cooler when I had to return to the fetid hold. It would dry soon enough. So would our skinny bodies which were then left sticky with moist salt but nevertheless, refreshed. Probably none was happier about our topside baths than the men on latrine detail. There were toilets on deck, wooden affairs built on platforms cantilevered off the deck over the sea. During the time we were allowed up there - 20 allotted minutes and if you were smart, an hour and a half - you could use them. That eased the work of the latrine detail. Now the air was different. It was hot because it was summer, but it had less of the heaviness of tropical air and more the pungency of the Temperate Zone. Islands on the Horizon... When we were topside, we could see a lot of little islands. Little, green punctuation marks in a blue, sea-story book. Those in the distance looked like little greenish dots peeking over the horizon. Some looked too small to have inhabitants, but the larger of them had buckskin tan, shore lines with slivers of fishing boats beached upon them. Later, the land fall was continuous and the shoreline longer with occasional interruptions that erased the sands now and then. We knew that we had reached a larger land. Our joy was not unlike that which gladdens the heart of any sailor who has been at sea for a long time and anxious to set foot on God's great, green earth. What we could see of it now surely looked inviting. Imagine our disappointment when, after we had drawn so close, that the ship dropped its anchor. Most of us would have gladly tried to wade or swim ashore, so anxious we were to disembark the terrible Nissyo Maru. Some in our hold knew that we had reached the port of Moji, Kyushu Japan, the southernmost of Japan's three big islands. The ship was later joined by a pilot and a small, harbor vessel, and pulled into and tied up to the docks. We had to wait all night while a Japanese longshoremen crew came aboard, opened the hatches and unloaded the sugar in the ship brought from Formosa (Taiwan). The noises of the winches and the yelling of the crew made too much racket to allow sleeping; we waited awake all night to disembark the ship. Vague thoughts of escaping now came to mind. It might have been easy to slip away in the confusion. One was not likely to be missed and the surrounding area looked inviting, but a Caucasian prisoner of war would have been as conspicuous as a cherry in a bowl of rice. One could not expect to be hidden and protected in the enemy's homeland which had been common for the brave escapees in the Philippines. Recapture would likely be swift and brutally final. Anyway, were we not guests of the Emperor? Guests in a land famous for gracious hospitality. Pitifully, they tried to make it appear so. Each debarking man was given back some of the clothing worn and carried aboard and dropped so unceremoniously into the hold some 17 long, hot days before. But no one got his own or, necessarily, a good fit. Some of us were handed smashed, gray and blue sun helmets of the old Filipino Army. As part of my "uniform," I received a pair of yellow-green Japanese army trousers, worn, soiled and threadbare, an oversized pair of army shoes and a ragged, dirty shirt that I thought would be better than nothing. One by one we were marched, or carried, over the gangway. It was not the brutal disembarkation we experienced when we first came aboard. As we reached the dock, a weak solution of some chemical was sprayed on and over each of us so that whatever vile disease we were bringing to the land of the Rising Sun would not infect them. The old technician who sprayed me did not seem very serious about it - just the normal operating procedure, I guessed. What most of us were suffering was the lack of good ripe apples, hard boiled eggs and fried chicken - to name a few of the medicines that would have restored and preserved what health we still had. Other writers such as Manny Lawton, Colonel E. B. Miller and Preston Hubbard have stated that the suffering of prisoners on hell ships was among the worst atrocities of the war in the Pacific. Hubbard writes, "...Hell Ships do not lend themselves to varied viewpoints or contrasting scenes. The damned, dark world of Hell Ships lies buried beyond the reach of memory or imagination." He feels that is the reason there has been no motion picture made of such an experience. There is nothing to compare it to and good art must have contrast. No doubt true in part but, nowadays, with the motion picture industry dominated by the Japanese, it is most unlikely any recollection of this phase of World War II infamy will be so recorded. As Dr. Hubbard so aptly writes, "Unfortunately, they (remembrances of Hell Ships) will probably vanish from the thoughts of mankind when the last survivor has gone to his grave". As I rewrite the lines of an original draft of this account, written almost 50 years ago, I can hardly believe how we suffered. I am repelled by the memory of the hideous voyage of the Nissyo Maru. I can scarcely believe it really happened anymore. It is not much consolation to consider that at least the torpedoes missed the ship we were in and no bombs from friendly war planes struck us as they did the Arisan, Orokyo, Enoura Marus and a number of others. Many prisoners were killed, drowned and died in these infamous ships. It is almost impossible to recall that among us were those who hoped our misery would end quickly by a torpedo that might mercifully explode into us with a flood of cooling, cleansing water, washing away the terror and the incredible filth and the noise of our teeming mass. It was, chilling as it may seem now, true and I can hardly expect anyone who was not there to understand or really believe it. The Lord was merciful to our group, most of us, anyway, and we survived. It was not the end of our suffering; we had another year of captivity still ahead. We knew that eventually the real horrors of war would reach Japan's precious homeland. We did not know that it had drawn as close as it had. Neither did we know very much about how terrible the reckoning would be for them. Now, in the Land of the Rising Sun, captivity as we knew it was a new dawning. Gone were the days where the fence was such a distance from where we slept that days might go by out of sight of even a single, enemy guard. This was true only in the large camps but even at Clark Field, the interface with our captors was often not long or frequent for some of us. It would be different here. From the moment we left the Nissyo Maru, the Japanese would be in "our face" constantly. We survivors of the voyage of the Nissyo Maru were lined up in units of a 100 each. What a crusty, filthy-looking bearded bunch we were. Any patriotic Japanese civilian thereabouts must have wondered what was taking his army more than three years to beat down such a motley enemy. Getting off that terrible ship was immense relief. A detachment of horse calvary stood by, apparently waiting to board the vessel after it had been unloaded. They were welcome to it, I'm sure, but I know they would not like it, especially the horses. I could not believe that any amount of cleaning, decontaminating or fumigating would make it fit for any purpose after we left it. I was amazed to learn afterwards that the Nissyo survived the war and plied the shipping lanes for some time after the war - the only "hell ship" to escape being sunk. Except for those who died during the trip and as a result of the stress later, it was a lucky ship and we survivors were fortunate to be in her and not one of the others. We were marched to an auditorium, a single story, wooden building badly in need of repair. We were assigned to sections and given a meal consisting of a rice ball mixed with a few, cooked soya beans and some kind of unidentifiable leafy vegetable that may have once been green but now was a deep, vile viridian after having been cooked in soy sauce. No matter, it was welcome and delicious but, we wanted water as much as food. "Don't drink the water in the washroom. It is polluted," we were warned. Nearly dehydrated now, we ignored the message. Our bodies must now be immune to Japan's friendly microbes. After those in the tropics, whatever we might encounter at this time could not hurt us much. Most would take the chance. I did and drank as much cool water as I wanted. It was almost too much to believe. The faucets were left running as men held whatever cup, can or bottle they could locate to catch a drink. Hardly a drop ever hit the floor. |

| Next: Chapter 7 - Full Text of MIKADO NO KYAKU (Guest of the Emperor) | Please Click Below for: |

| 1. Introduction to Slavery | Page 1 |

| 2. Our New Home in Bongabon | Page 15 |

| 3. To the Shade of Mount Penatubo | Page 37 |

| 4. Bilibid Prison Again | Page 55 |

| 5. Cabanatuan "Revisited" 1944 | Page 59 |

| 6. The Nissyo Maru. A True Trip of Terror | Page 67 |

| 7. Where the Birds Don't Sing and Flowers Don't Smell | Page 82 |

| 8. The Setting of the Rising Sun | Page 99 |

| Epilogue | Page 117 |

| Return to MIKADO NO KYAKU Introduction Page |

| Additional Fourth Marines Photos and Information |

| Please Click Below To Return To: |

| EMAIL: info@4thmarinesband.com |

| ©2000-2021 lastchinaband.com. All rights reserved. |